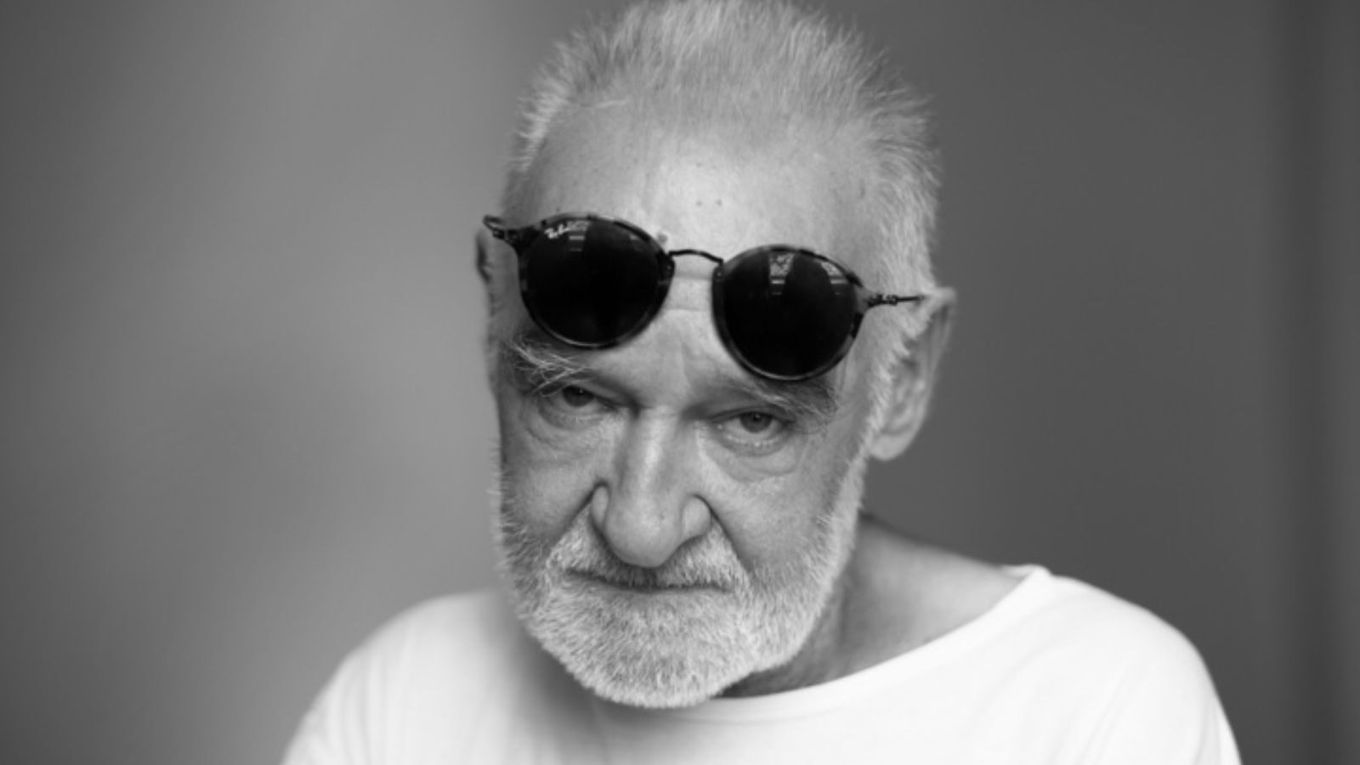

Béla Tarr

Director

2025

Motivation

In the year of the European Capital of Culture, we have decided to give the Darko Bratina Award to Béla Tarr, the magnificent Hungarian filmmaker who knew how to tell the story of the curse and resilience of a world that has collapsed. He has travelled the world with his films and shown that film is created along paths of freedom, dialogue, and poetry, and through the independence of unconventional, demanding, and dynamic choices. Tarr has paved the way for a different view of film with his creative work, which transcends the borders of countries and languages. His vision has opened up the space for thinking about history, society and art, and teach us that film is a place where cultures, memories and human destinies meet.

Biography

Béla Tarr, a director from Hungary, where almost all of his films are based, made his first feature film, The Family Nest (1979), at the age of twenty-four. He retired the handheld camera, and his youthful anger has calmed down over the years, but has become deeper. The epic Sátántangó (1994), a seven-hour and twenty-minute long film shot on the Hungarian plains and awarded the Silver Bear, brought him worldwide recognition. His films go beyond narrative and create a rhythm and dimension, reminiscent of Ford or Melville, even if without direct influences. Although they come close to Tarkovsky or Jancsó, his films follow their own path, imbued with a political and humanistic dimension – as in Prologue (2004) or Werckmeister Harmonies (2000). With The Turin Horse (2011), he consciously concluded his film career. He then devoted himself to art installations and teaching between Sarajevo and Prague. As one of the most elusive yet most celebrated creators of his generation, he remains a symbol of auteur cinema, even though he evades this label.